Jefferson County, Mississippi

Jefferson County, MississippiA Proud Part of the Mississippi GenWeb!

Contact Us:

State Coordinator: Jeff Kemp

County Coordinator: Gerry Westmoreland

If you have information to share, send it to Jefferson County MSGenWeb.

In the menu on the left there is an index of Military Records on our website.

Jefferson County, Mississippi, in the American Civil War

USS

Rattler at Rodney, Sunday, September 13th, 1863

By Bruce D.

Liddell

After six generations few military traces of the

American Civil War 1861-1865 survive in Jefferson County, Miss. One

scar remains today for all to see, a Union cannonball imbedded in

the brick front wall of Old Rodney Presbyterian Church.

The

Civil War passed lightly over Jefferson compared with other parts of

the South. No great battles or orgies of destruction occurred within

the county, but nonetheless “cruel War” left its evil mark. Ravenous

armies stripped the land of livestock and food, taxation and

inflation stripped the people of their money, and slaves themselves

stripped off their bondage at every opportunity. War and

Reconstruction also stripped away the South’s cloak of prosperity

leaving bare poverty, but that’s another issue.

Before the

Civil War Rodney ranked as the largest town in Jefferson, erstwhile

contender for the state capital, at one time reckoned the busiest

river port between New Orleans and St. Louis. After the War the

Mississippi River shifted a few miles west, leaving the town high

and dry. Today Rodney has all but withered away, leading some to

call it a ghost town, though the last remaining resident reportedly

disputes that.

In the summer of 1863 Union forces seized control of the

Mississippi River and cut the Confederacy in two. Vicksburg

surrendered on the Fourth of July (and never again celebrated the

holiday until 1944) and Port Hudson, La., four days later, severing

the Trans-Mississippi states from the Richmond government. For the

next two years Federal warships patrolled the Father of Waters to

shut down all Confederate river traffic. During most of this period

the “tinclad” gunboat USS Rattler enforced Washington’s will at

Rodney and vicinity. (1)

USS Rattler was one of sixty-odd

mixed-bag riverboats purchased and armed by the U.S. Navy, called

“tinclads” to distinguish their bullet-proof qualities from the

heavier cannon-proof ironclads. Drawing on average only 4 feet of

water, the tinclad fleet flaunted the Stars and Stripes with

near-impunity along the Western Rivers. Named for the poisonous

snake, Rattler began her career as the smallish 165-ton stern-wheel

flat-bottom steamboat Florence Miller. (One wonders what humorous

combinations the sailors made from the gunboat’s names.) Designated

Tinclad Gunboat No. 1, she cost the government only $24,000,

one-tenth the price of a purpose-built warship. (2)

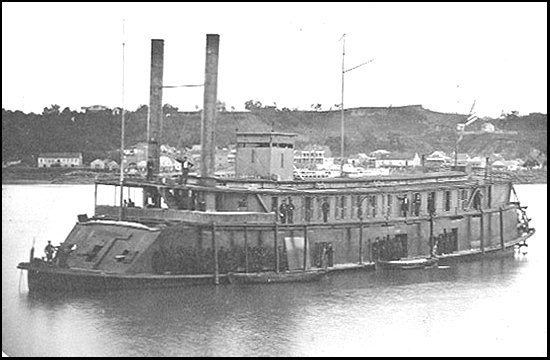

USS Rattler at anchor between July 1863 and December 1864. The

vertical mark on the front and side of the pilot house is her

numeric designation, Tinclad No. 1. One authority has identified

the background as Natchez-Under-the-Hill. (3)

USS Rattler

grossly resembles a two-story flat-roof boarding house for thirty or

forty resident crewmen. About 100 feet long and 30 feet wide, her

exact dimensions and internal layout are unknown but can be

surmised. The topmost (texas) deck was removed and replaced with a

rectangular enclosed pilot house. Officers and enlisted men ate and

slept in the former passenger spaces upstairs (hurricane deck) above

the engines on the newly enclosed main (cargo) deck. Hull spaces

remained empty, as riverboats’ flat bottoms sagged under load. Three

guns protruded from an angled casemate at the front (bow) of

Rattler’s cargo deck, one long range Parrott rifle firing 30-pound

shot flanked by two 24-pounder Napoleon smoothbores. Presumably an

identical battery pointed sternward over the paddlewheel. Shielded

all around by heavy timbers, she also carried one or two thicknesses

of half-inch iron plate armor over the forward battery casemate and

around the pilot house. By her mobility and protection virtually

invulnerable from attack by land, Rattler could out-fight every boat

on the river except the heaviest ironclads. (4)

After three

summers of war and slaughter autumn 1863 loomed blessedly peaceful

along the Mississippi River. As the sun rose on a quiet fair-weather

Sunday, September 13th, 1863, USS Rattler lay at anchor near the

Rodney town wharf. Stationed at Rodney since mid-August, she had

returned the previous day from a short visit to squadron

headquarters at Natchez. That Sunday morning Rattler’s captain

Acting Master (modern Lieutenant Junior Grade) Walter Fentress

welcomed a guest on board. Reverend Baker, a Union man, had recently

resigned as pastor of the Red Lick Presbyterian Church and presently

awaited a passenger boat headed “North,” meaning any district under

Federal control. Reverend Robert Price, long-time pastor of Rodney

Presbyterian Church, generously offered his pulpit and collection

plate to Rev. Baker that Sunday. Baker in turn invited Rattler’s

officers and crewmen to attend morning services at the church. (5)

In violation of Admiral David Porter’s standing orders, at 11

a.m. Captain Fentress led most of his crew ashore. None were armed

except Second Assistant Engineer A. M. Smith, who carried a hidden

revolver. All sported their Sunday best; Fentress wore a plain

civilian coat, perhaps to avoid arousing the nominally hostile

citizens. An officer in civilian dress in enemy territory during

wartime runs a terrible risk, and one wonders if Fentress clearly

understood his position. (6)

About 10 minutes after the

worshippers found their pews, Lieutenant Allen of the Confederate

Army walked into the church, interrupted the services with a polite

apology to Rev. Baker, and ordered the U.S. Navy men to surrender. A

noisy fracas ensued. (7)

Perhaps Rattler’s men made a habit

of attending Rodney Presbyterian Church, or possibly a Southerner

named Billy Parsons carried Baker’s invitation to the nearest

Confederate outfit. By one romantic account Lt. Allen donned

civilian dress, silently entered the church and counted the sailors

from the back pew, then slipped outside to change clothes and alert

his men. While music and voices covered any sound Allen directed his

fifteen Confederate scouts to surround the building, then strode

boldly through the church front door. (8)

At the call to

surrender, Engr. Smith drew his pistol and fired one shot through

Lt. Allen’s hat (though this may be an editor’s fanciful phrase for

any near-miss.) At the sound of gunfire inside, the Confederates

outside fired through the windows, all the balls striking the

ceiling or opposite wall. Smith shot three more times, and as fast

as they could reload the cavalrymen pumped more rounds harmlessly

through the shattered windows. Allen discharged his revolver once

into the ceiling, shouting for all to cease fire. (9)

No

doubt confusion and fright reigned among the unwilling participants.

The Jackson Mississippian applauded one strong minded matron who

stood her ground, shouting “Glory to God!” as the Rebels overpowered

the Yankees. One sailor tried to hide under the voluminous skirts of

elderly and immobile “Mrs. I. D. G.,” and other Navy men entertained

similar thoughts. Although several modern writers describe a happy

marriage that resulted from the unwonted intimacy, no confirmation

has been found. The tale may have arisen from the Depression-era

“urban legend” of an ancient Union veteran who went searching for

the long-deceased lady who saved his life in a fight inside a

church. (10)

Lt. Allen finally made himself heard above the

noise. The Rebels stopped shooting and rounded up their Yankee

prisoners. By a seeming miracle, only one seaman received a minor

wound. Allen commandeered civilian carriages for the Union officers

and started the Union sailors marching single file out of town on

the northeast road toward nearby Oakland College, closed and empty

since the outbreak of war. The civilians quickly scattered to their

homes. (11)

Alerted by the gunfire and informed of the cause

by “a negro on shore,” at 11:20 a.m. USS Rattler’s first lieutenant

(modern executive officer or “number one”) Acting Ensign William

Ferguson sent the remnant crew to battle stations, got the gunboat

moving, dropped a boatload of armed sailors to secure the wharf, and

ordered the gunners to open fire. Rattler’s cannons threw fourteen

explosive shells into the town, setting several small fires and

damaging the church and four houses. One shell damaged a barn on

nearby Pecan Grove plantation. Amid the smoke and concussion six

Navy men including combative Engr. Smith escaped to Rattler’s

waiting boat. Ens. Ferguson ceased fire when Lt. Allen’s party and

prisoners were out of sight. By 1:30 p.m. the initial excitement had

passed and Rattler again lay at anchor, but now in deep water. (12)

To his eternal embarrassment Fentress holds a unique

distinction, the only United States Navy ship’s captain captured by

Confederate States Army horse cavalry. (13)

Later that

afternoon Ens. Ferguson decided to burn down a Rebel’s house in

town, after Seaman John Henderson, one of those who escaped,

reported he “was driven from thence by the owner.” Ferguson detailed

an officer, probably Acting Pilot George G. Waggoner, and a boatload

of armed sailors, probably including Henderson, for the job. Rattler

fired eleven more shells to cover their operations. Word of the

incendiarists reached Lt. Allen, who threatened to capture the

outnumbered landing party and hang them as arsonists. (See

discussion of Lt. Allen's threat below.) The sailors meekly returned

to the gunboat, their task left undone. (14)

After dark

Rattler received a petition from ”the principal citizens of Rodney”

begging the U.S. Navy to hold the town blameless, as the townsfolk

had no prior knowledge of the noontime affray. At 10 p.m. that night

a civilian emissary, Dr. Goldsmith, brought a message from Capt.

Fentress requesting clothing for the captives, to be delivered to

Crystal Springs 60 miles away; presumably this was done. Three days

after the ambush Rev. Price and thirty-seven townsmen (unnamed)

signed another petition, Adm. Porter relented, and thus Rodney

avoided the vengeful destruction normally practiced by Union forces.

(15)

Except for one Union cannonball still imbedded in the

brick front wall of the Old Presbyterian Church in Rodney, Miss.

(16)

Epilogue. Some months later Fentress and his men were

exchanged for a like number of Southerners, and resumed their Navy

service at other posts. At the end of 1864 USS Rattler sank near

Grand Gulf, Miss., in a storm, her crew saved but the gunboat a

total loss. In 1930 Gov. Bilbo extinguished the Town of Rodney. In

1966 the United Daughters of the Confederacy took over the Church,

and in 1990 dedicated the building as their Official State Shrine.